This is a review from March 2013.

Refugee Boy is now on a national tour and is about to start a new run at the West Yorkshire Playhouse.

So I thought it was an ideal time to dust this interview off!!

ALEX CHISHOLM

WEST YORKSHIRE PLAYHOUSE

ASSOCIATE DIRECTOR (LITERARY)

Leeds

Book Club caught up with Alex Chisholm a few weeks ago, for a quick chat

between putting the final touches on Refugee Boy and collaborating on Sherlock

and Doctor Faustus.

Refugee Boy will open on the 9th of March and run until the 30th. Copies of the play and book will be available from the Playhouse.

The interview will be posted in two parts. This section shall focus on Refugee Boy while part 2 will look at the inner workings of the Playhouse.

Thanks very much for

taking the time to speak with us. We appreciate that must be incredibly busy at

the moment.

Refugee Boy is a 2001

novel by Benjamin Zephaniah about a

young adult named Alem. He is abandoned in the UK due to conflicts in his

country of origin.

How does something like this

production of Refugee Boy get started? Does a writer or director approach you?

It

happens in all sorts of different ways. In this particular instance it was our

associate Director that deals specifically with young people and their theatre.

She knew Benjamin Zephaniah and the book and said ‘I’d like to do a version of

this’. Looking back through old files the other day, I came across my original

document that had a list of potential adaptors. I came up with that list, we

talked about it, we liked Lemn Sissay (a poet and playwright) – it turned out

that he had himself a very similar history so that all dovetailed very well

with the book. It’s been a very long journey getting it to this place for all

sorts of different reasons.

It’s

pretty much there now. Final few tweaks to do. It’s pretty much there. Then

again, it’ll change again in rehearsal. And it’ll open on the 9th of

March with its first performance with rehearsal beginning about four weeks

before that.

Refugee Boy – is it an accurate

portrayal of the Ethiopian and Eritrean conflict?

There

isn’t, in fact, in the book that much detail about the nature of the conflict

and the little bit that’s in there isn’t necessarily terribly accurate, but

that’s not the point of the book. The point of the book was to follow the

journey of the Refugee Boy himself.

The

two tiny flashbacks that he does in Ethiopia and Eritrea – the whole piece

takes place in England – there’s this

sort of prologue of two tiny snippets and they are intentionally abstract and

not realistic and very similar to each other another.

Benedict

– one of our contacts – is himself from Ethiopia and Eritrea and he came over

as a young man – not quite as young as the character in the book. Benedict says

that you can pick at it; you can tear away parts and say ‘Well actually that

wouldn’t really happen that way’ but on the other hand he read that book as a

sort of alternative narrative of his own life because essentially the story was

his and a lot of the emotional journey and the journey of adjustment to a

different country was absolutely his.

You

wouldn’t read Refugee Boy in order to gain insights into the Ethiopian and

Eritrean conflicts. You do so in order to gain insights into what it is to be a

refugee, an asylum seeker in this country.

Refugee Boy – the Charity

sector

Since

getting involved with this particular project, we’ve become much more in

contact with the org and people and agencies that work in that area in our

region. We’ve been struck both by the immense generosity and hard work and

selflessness and kindness of people who work and volunteer.

And

also about the terrible circumstances and deprivations which go along with

that. In particular destitution being the big issue we’re dealing with at the

moment – there’s a particular thing that’s happening right at the moment with

the way that housing is changing which –

I imagine you’re aware of – it’s causing particular problems.

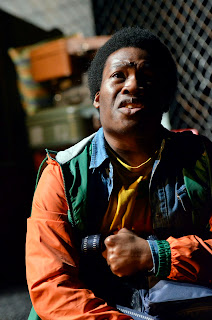

Refugee Boy – won the

Portsmouth Book Award – and certainly caught the zeitgeist. Author Benjamin

Zephaniah is renowned for his music, poetry and writing. This is a particularly

inherently human book revolving around isolation, alienation and finding your

own place in the world.

|

| Benjamin Zephaniah |

Have you spoken with him

about the book or the WY Playhouse adaptation of it?

I

haven’t spoken to him directly to him about it. However, I’ve read and heard

him speak about it. I don’t know if there was a particular incident that got

him interested in this but I know that he himself felt empathy for people who

have gone through that experience. Coming from a Caribbean background, but one

where he felt that he understood that isolation and being misunderstood as a

young person. He also has a keen sense of justice that comes from his

background and having experienced injustice. As a Rastafarian, who is

practising and religious and spiritual; he particularly had an interest in this

journey. [That of] seeming outcast and that essential notion of finding a

family.

The

Ethiopian and Eritrean conflict was reaching a certain point around the time

that he was writing it so there was a public awareness at that time.

How did you find the

right playwright to adapt this novel?

Lemn Sissay who did the adaptation,

is also a poet. Actually it’s one of those strange coincidences that happen in

life. I had read a play of his called Storm I think (written for Contact theatre in Manchester) and it was

set in a children’s home and I felt that it captured the voice of those young

people extremely well. It was his first play and incorporated some poetry into

the play writing. And he wrote those young people in a well rounded,

un-clichéd, unsentimental way – which is very rare.

They

were first and foremost young people and they happened to be in a situation and

they reacted to that situation. Rather than them being types. That’s what made

me think about him in the first

instance. Because there is a part of the book where Alem goes to a children’s

home and then a foster home so writing a piece where the main character is a

young person. He’d directed a lot of young people. There was something in Lemn’s

writing where I felt that he could find that character.

So

I called him up, said that we were interested in adapting this book called

Refugee Boy by Ben Zephaniah and had he heard of it? He said no, what’s it

about and I summarised ‘it’s about a young boy, born half Ethiopian and half

Eritrean, abandoned in this country and raised in the care system’. And he just

exclaimed ‘You’re kidding me. That’s my life.’

And

that is, it’s genuinely his life. He is half Ethiopian and half Eritrean, his

mother came to this country to give birth to him here and then abandoned him

here and went back. Lemn’s gone on a huge journey – which is quite well

documented – to discover what his past is. And he started off in a children’s

home; was then fostered; then he was essentially rejected by his foster home;

returned to the children’s home; grew up there and left at 18 years and that’s

when he was given his papers. This was when he discovered his birth name. He’d

had a completely different name up until the age of 18. He gravitated towards

Manchester, discovered poetry and found his voice and became, or was kind of

taken up by John G at Contact and given a lot of support. Discovering that, he

felt that he was the right person to take this on. He has brought a lot to the

adaptation.

On making necessary

changes from the original

There

are some aspects of the play that are not actually in the books, but this was

right. If you read the book, it reads very well but there are certain things

missing that you’d want for a play. It’s telling you a story but the additional

insight from any other characters apart from Alem can only be inferred.

It

works in a novel but not as naturally as a play. So you don’t necessarily know

what’s going on with Ruth or the foster parents. Basically they are ciphers.

Although you do get a bit more from Alem’s father – the relationship between

the two is fairly straight forward. There isn’t that much change in it.

|

| Lemn Sissay |

So,

Lemn has sort of added aspects to that; while retaining the story of the

refugee boy; keeping the central premise of the piece, but there’s a very

strong relationship between Alem and a friend of his from the children’s home

that is totally invented. It doesn’t exist in the book.

You

need people for your central character to talk to. Otherwise it’s a one man

show. And funnily enough, Lemn has already done that show. He did it about his

own life. It’s called ‘Something Dark’ and

it’s absolutely brilliant. It’s a one man show.

But

he’s done it. It’s not actually about refugee or asylum but about a young man

coming to terms with having been abandoned – the search for identity.

You

watch that show and think ‘you’re still standing?’ So I think it’s really…now

we’re at a place where we have I think a really good play from a really good

book. They are going to be there own

things. Benjamin Zephaniah has read the play and was happy with it. He found it

a bit strange – in that it is and isn’t his novel.

Different

people have different levels on control. Benjamin has been very open and relaxed

which has been lovely. It’s very good that it is happening.

Did you ever doubt that

it would all come together?

The

thing is that there is a burst of activity and then there would a long long

while where nothing happened at all and then there’d be another burst of

activity and then a long long while where nothing happened at all. But we’ve

got the momentum back.

[All

of this is of course worthwhile as] I think it is a play that will engage a lot

of different people in a lot of different ways. I think that there are a lot of

people who are broadly sympathetic to the issue around refuges and asylum

seekers and will be interested in it for that reason. I think that there are

people who will be interested in it because they’ve heard of Benjamin Zephaniah

or enjoy his poetry and his writing. And maybe people who’ll try it because

maybe their kids had to study it in school and hopefully they will bring them

along.

I’m

hoping that it will reach out to quite a broad audience.

Now the production is

coming together, how involved are you at this point?

To

an extent…personally I’m less involved now that the director Gail McIntyre [has

taken the reins]. Certainly less once it goes into rehearsals. I’ll be coming

to see it towards the end of rehearsal and once it goes into preview. I mean

I’m very involved in how the events are happening so I’ll be working through

the whole time and I’m probably more involved in this one that others because

I’ve been so involved in the making of it. We’ll see. It depends on how much

Lemn wants to be around. Whether there’s a need for me to manage the dynamic

between how much you want it to be changed, how much you don’t want it to be

changed.

Every

production is different and needs different kinds of support.

Touch wood – it’s a huge

tremendous success. Will it tour?

Our

aim is to tour it the following year if we can make everything work out.

Because Benjamin is a successful writer and that is a very popular book – it’s

studied in schools – there is a certain amount of interest from other theatres.

That’s the idea really. We’ll see; we’ll see what happens.

It’s

not even always down to whether it’s a success. It’s down to money and what

budgets are like and what other plays have been planned for [for other

theatres].

And

then of course, it’s onto the next stage of the project.

Well best of luck with the opening. And thanks so much for chatting with

us.